Greater Boston Housing Report Card finds recent efforts unable to make major dent in region’s segregation, housing cost issues

High costs, resistance to affordable development in suburbs help drive segregation in post-redlining era

June 26, 2019

Boston– An examination of the Greater Boston housing markets finds that efforts to undo the legacy of redlining have not been enough to fix the region’s housing equity and segregation issues. The report,The Greater Boston Housing Report Card 2019: Supply, Demand and the Challenge of Local Control, was produced this year as a partnership between the Boston Foundation, the Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy at Northeastern University, the Massachusetts Housing Partnership’s Center for Housing Data and the University of Massachusetts Donahue Institute.

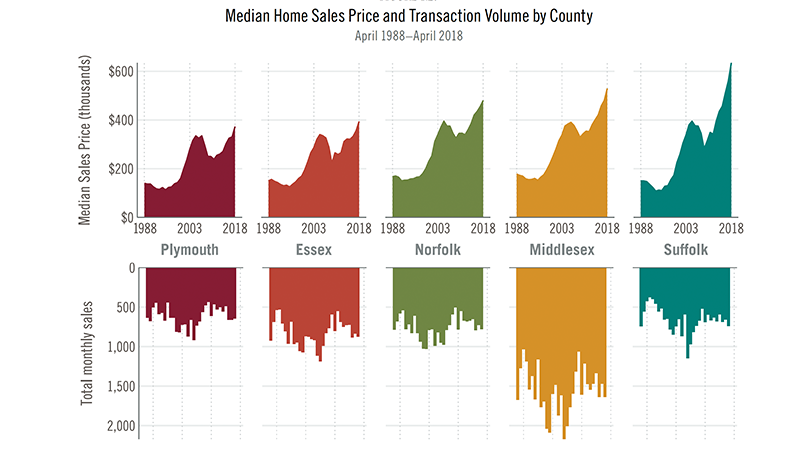

For 2019, the report digs into the changes in housing demand, supply and affordability in Essex, Middlesex, Norfolk, Plymouth and Suffolk Counties, and the impact of the housing shortage on housing cost, displacement and racial segregation across the region. Over more than 120 pages, researchers look at the current state of the Greater Boston housing market in terms of affordability across income levels, the development of new housing, and looks at possible policy alternatives that could help reverse the legacy of segregation in housing that plagues Greater Boston and many other regions. In addition, the report provides a “report card” snapshot for each of the 147 cities and towns of the region compared with the region as a whole in five key areas: local housing production, adoption of best practices, affordability, housing stock diversity, and racial composition.

“Despite well-intentioned and long-continuing efforts to improve housing affordability and equity across the region, it’s not an earthshattering surprise that Greater Boston has a great deal left to do when it comes to addressing the legacy of social and economic segregation,” said Paul S. Grogan, President and CEO of the Boston Foundation. “What may be surprising is the level to which overt redlining tactics designed to keep racial and ethnic minorities out of some areas has been replaced by economic, social and zoning barriers which still make housing diversity difficult, impracticable or impossible in many communities.”

“Greater Boston’s struggles with creating and preserving affordable housing across all income levels is both striking and well-known,” notes Alicia Sasser Modestino, Associate Director of the Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy at Northeastern University and the lead author of the report. “By looking at housing affordability alongside an examination of segregation data and tracking how local governments are seeking to address the issues of production, affordability and equity, we can see a more nuanced picture. It shows limited progress, but also a need for a redoubling of local and state efforts to make changes to zoning and development rules that slow progress and result in greater segregation, a lack of affordable housing and an increase in homelessness.”

Understanding the current housing environment

The report finds many facets to the current housing crisis. Greater Boston’s population continues to grow – almost entirely because of international immigration into the region – creating a more diverse population but putting a greater strain on current housing stock. Housing affordability lags sharply, not just on account of the region’s often-highlighted income inequality, but because the region’s low vacancy rate and relative lack of new construction combine to make housing less affordable at every income level.

A lack of permits plays a major role. While the number of annual permits issued in Greater Boston is near where it was before the Great Recession, Greater Boston lags almost every other major metropolitan area in terms of the number of new permits issued and new units entering the market, and data show the majority of new permits in the state since 2013 have been issued in just 15 communities, with more than half of the new multifamily housing permitted statewide since 2013 being concentrated in just four cities and towns, Boston, Cambridge, Everett and Watertown. Overall, recent activity falls short of projected housing needs through 2025, with production varying sharply between communities.

Meanwhile, ownership and rental vacancy rates are below not only the national average but also below the 2 percent “stable vacancy rate,” leading to price pressures. Home prices and rents have risen sharply across the five-county region – Boston trails only San Francisco and Los Angeles in median rent for a 2-bedroom apartment, and while foreclosures are down across the region, the identified homeless population has risen by 27% for families and 45% for individuals in Greater Boston over the past decade.

With pressure mounting, housing prices are have risen sharply throughout the region at all levels of the price spectrum. Monthly sales volumes have not kept pace with the sharp increase in prices.

Meanwhile, despite an often-stated goal of increasing housing availability near transit as a means to provide housing without increasing traffic congestion, the research finds communities with rapid-transit access still comprise just 46% of permits issued, and multifamily permits in those communities concentrated in a small number of communities. The signature legislation for this transit-oriented development effort, Chapter 40R, has only had limited impact.

Best practices and a look at segregation

Despite the concerns raised by the data, there are a number of best practices that communities have been able to put into place on their own, a result of the unique control that communities have over local planning and zoning. Almost all communities in Greater Boston have zoning that permits multifamily construction in some areas, and dozens of communities have opened up the possibility for multifamily zoning. A growing number of communities have created zoning for accessory dwelling units (often referred to as in-law apartments or “granny flats,”), and increased zoning for mixed-use development, and elements like inclusionary zoning, requiring the development of more affordable units, and trust funds for affordable housing, have become more common. However, many of these programs have shown limited impact, and the number of cities and towns adopting age- or other restrictions that limit affordable housing growth has risen, as well.

In the end, despite decades of work to reverse the legacy of practices that enhanced racial and economic housing segregation in Greater Boston, the region has seen only limited improvements in indicators of segregation. Greater Boston as a whole has become more diverse - earlier research from Boston Indicators notes that every Greater Boston community has a higher minority population than it did in 1990. However, when the researchers looked at a subset of U.S. Census Bureau measures for segregation, they found that metro Boston remains highly segregated for Blacks, with moderate to high segregation for Latinos and moderate segregation for Asians. The research finds Boston is less segregated than New York across all racial groups, less segregated than Chicago for Black and Asian groups, but more segregated than San Francisco for Blacks and Latinos and more segregated than Seattle among all groups.

Metro Boston’s overall segregation levels improved slightly across all three groups in 2017 compared with 2000 and 2010.

Understanding our current segregation challenges

What explains this persistent segregation? The authors first looked at the role of economics in this segregation, and found similar maps of segregation and poverty in the region, including 68 urban census tracts in Greater Boston with both concentrated poverty and concentrated segregation. However, the authors note that while both rising income inequality and widening racial disparities in income play a role in racial segregation, controlling for these factors does little to change segregation patterns across municipalities.

Using a measure developed by the Census to measures the predicted, or expected, number of people in each group based on the region’s income distribution by race to where people of different racial backgrounds actually live, the researchers found the racial segregation in Greater Boston is receding, albeit at a very slow pace. As a result, more than three quarters of the cities and towns in Greater Boston have Latino populations that are severely below the levels expected based on their income distribution. Roughly 67 percent of municipalities have black populations that are severely below predicted levels and 54 percent have Asian populations that are severely below predicted levels.

The authors also explore the link between housing production and segregation. Communities experiencing greater reductions in segregation between 2000 and 2017 were those that permitted more housing units. However, the relationship does not hold uniformly across all types of housing, but instead is related to the supply of multifamily housing. In addition, those communities that came closer to meeting the 10 percent threshold for their subsidized housing inventory also saw a reduction in the share of the population that was white. The authors conclude that not only is it necessary to build a mix of housing types but also to ensure that housing is affordable to a more diverse set of individuals and families.

Changing the dynamics to reduce persistent segregation

Reversing this trend, the authors suggest, requires addressing housing supply, affordability and equity. The authors say zoning reform, such as the Housing Choices bill currently in the Legislature, could be an important first step by lowering the bar for approval of zoning changes to enhance housing production. However, more could be done legislatively to support multifamily housing, accessory dwelling units and other higher-density housing.

Affordability, however, goes beyond production, and the authors note the importance of protecting currently affordable housing stock and expanding efforts such as inclusionary zoning during this strong housing market to require developers to provide a larger percentage of affordable units in the current boom.

On equity, the authors suggest the state could step up efforts to support minority home buyers through financing supports, and also strengthen enforcement of anti-discrimination laws to both block intentional or unintentional discriminatory impacts of zoning changes and address zoning rules that are biased against rentals for families with children, which effectively discriminate by income and race.

Lastly, the authors note, there is a need for more consistent data collection –to ensure consistent reporting of zoning and assessment data, and up-to-date reporting of basic property-level data which would allow improved analysis of how housing development intersects with important attributes such as access to transit or walkability. Local data sharing with the state, the authors note, can ensure that the Commonwealth’s billion-dollar investment in affordable housing is achieving the greatest possible impact.