The COVID Crisis: One Year Later

On the Ground in Chelsea and East Boston

April 30, 2021

Gladys Vega has been praised in the Boston Globe and other media for her steadfast work helping Latinx immigrants survive the pandemic in Chelsea, a city often described as “Ground Zero” for the COVID crisis. As Executive Director of Chelsea’s La Colaborativa, she and her staff have helped thousands of Latinx immigrants—providing food, clothing and any kind of shelter they can find. But the relief work that began at a fever pitch in March of 2020 is still extremely demanding and Vega and her staff have paid a high personal price for the anxiety that comes with feeling that they are still not doing enough.

“At times I feel that I set people up to fail because I’m placing them in an apartment they have to share with 14 other people in the middle of a pandemic or putting them up in a hotel that is only a temporary solution,” says Vega. “All I read about and talk about and think about are the people I am not able to serve, the people we are leaving behind. The people who have nothing—and rely on us for everything.

“Of course, we try to do whatever it takes to raise our community up, but we’re picking them up from a community that was totally neglected even before the pandemic. Yesterday I was thinking about a young man who was standing in the rain waiting for food. The supplies promised to our food pantry had not arrived, but people continued to wait and were getting drenched. We told everyone to give us their addresses and promised to deliver food by 11 p.m. that evening. One young man continued to stay. He said he didn’t have money for a bus back to East Boston and he was responsible for providing food for his mom and his sisters. He said, ‘Please don’t send me home emptyhanded.’ I have hundreds of heartbreaking anecdotes like that—about people who have hit rock bottom.”

An equitable recovery seems elusive to Vega: “The rollout of the vaccination program was not equitable. With the diversity and level of poverty we have in Chelsea, why weren’t we a priority?” While Chelsea originally was slated to receive only $11 million from the COVID-19 relief bill, in response to advocacy on the part of Vega and other Chelsea leaders, the amount was raised by Governor Baker to $20 million.

“I feel optimistic now,” she says. During the hardest times, she has taken inspiration from the resiliency of the people she is serving. “I have seen so much generosity. One woman said, ‘I have been coming here for food every week. Can I volunteer so that I can earn the food I’m taking home?’ That gesture was a beautiful thing. With all of the bad things that have happened in the city of Chelsea, the best thing for me was that, in the worst of circumstances, people wanted to help. I was moved by the response of strangers who came and supported our movement. They didn’t think about the fact that they were helping to feed undocumented immigrants. They were just helping human beings. That kind of generosity—that desire to help and heal other people—that has been my light.”

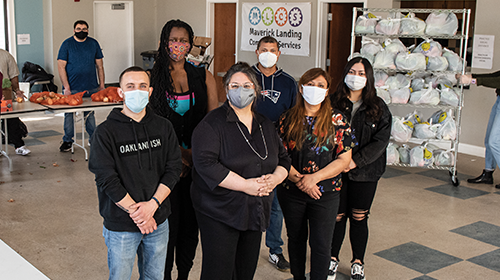

Rita Lara received a Champion Award from Mayor Walsh for her work during the pandemic. As Executive Director of Maverick Landing Community Services, she helped organize a collaborative of East Boston organizations to provide relief and food to those in need during the pandemic, including those who do not qualify for benefits, such as undocumented immigrants.

“If the starting point for the recovery is the vaccine rollout,” says Lara, “then it hasn’t been very equitable. We’ve been distributing food for over a year now and none of the frontline people who have been working so hard and risking themselves were qualified for the vaccine until recently. What is clear is that decision-making systems require pressure to respond equitably.

We know the problems we need to solve are systemic; they’re entrenched in racism; they’re entrenched in approaches that de-prioritize people who are poor, people who are Black and Brown. How do you change that? Systems are recalcitrant to change and require consistent pressure to reform and evolve. We can all be active in that work.”

When asked about recovery, she says, “Honestly, the first thing I thought of when everything happened last March was that this is the time to build. I saw food systems getting disrupted. Disruptions create opportunities. We didn’t even have a food program here. I could barely get an apple that first week and now we’re moving over 50,000 pounds of surplus food every month with local partners. It was the perfect landscape for scaling up and has had the added benefit of addressing food insecurity in a way that also has positive environmental impact.”

One area of hope is Lara’s work helping people generate income. “East Boston is an immigrant community that struggles with worker eligibility due to their immigrationstatus,” she explains. “But there are many ways to generate an income. People can be entrepreneurial and work for themselves— own their own business.” There are “workarounds” that she and others were pursuing pre-pandemic, such as helping people get an Employer Identification Number or an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number, so that they can legitimize their income by making it taxable and by demonstrating that they are a not a public charge. This better serves people on the path to citizenship. That goal is still high on her list.

What Lara calls “the benefit of now” is that grassroots organizing and advocacy in response to the pandemic, which was always strong in East Boston, is even stronger now and more highly organized. “We’re seeing emergent new responses, such as the mutual aid phenomenon. People coming out and forming networks. Much of this has happened digitally in informal networks that are loosely organized. These are organic, resilient responses to the pandemic. We need to keep responding resiliently. That is the path to recovery.”