STARTING FROM BIRTH

Black Philanthropy Fund

An Edited Transcript of a Conversation with

Members of the Black Philanthropy Fund, Boston Foundation Donors,

for the 2017 Boston Foundation Annual Report:

The Problem Solvers

How a Group of Unusually Creative Philanthropists

Are Helping to Solve Some of Boston’s Big Problems

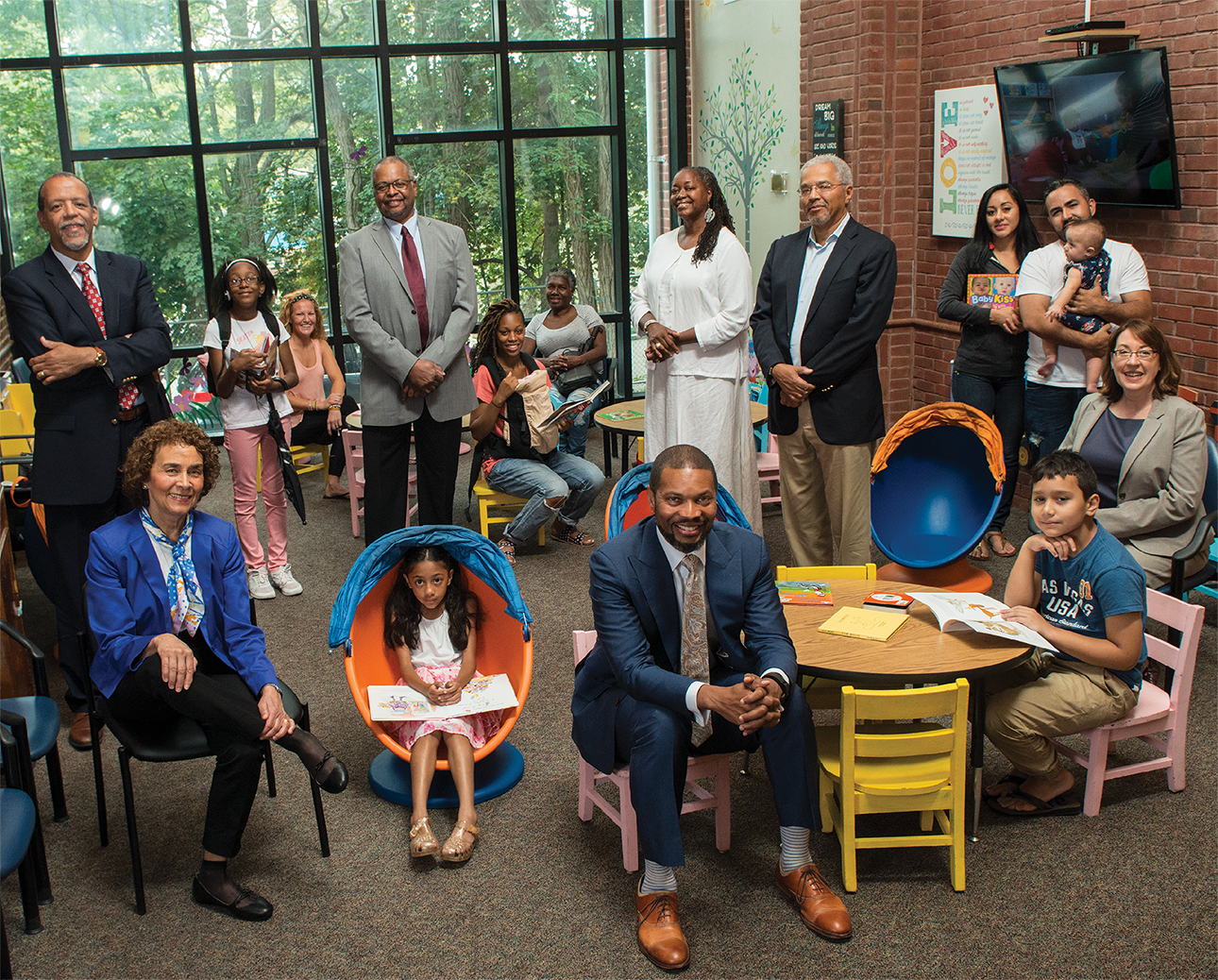

The Boston Foundation met with several members of the Black Philanthropy Fund on August 7, 2017, at the Dimock Center to talk about the Fund’s relationship to the Boston Foundation and to learn about the evolution of its initiative, the Boston Basics Campaign. Members arrived at different times, and join the conversation along the way.

TBF: How did you come to choose the Boston Foundation as the place that would house the Black Philanthropy Fund?

Wendell Knox (WK): We knew that we wanted a relationship with an organization like that, so that we didn’t have to build infrastructure, and we knew that the Boston Foundation was engaged in many community initiatives that were generally of the nature that we resonate with. We just felt that that would be the right kind of place to not only manage our money but to develop a partnership. In fact, we knew that we were going to want to try to entice the Foundation into becoming a more active partner―a funding partner, a programmatic partner, a thought partner. So quite apart from the money management―which, yes, we could have taken it to Fidelity or a lot of other places―we saw a lot more value in establishing a relationship there.

Many of us were engaged in some aspect of education anyway. Jeff Howard, who became our chairman, is the founder and president of the Efficacy Institute, which focuses on education reform and improvement. I’m on the board there, and we were classmates way back when, so we knew that we were going to advocate for the group to focus on some aspect of education. But it wasn’t a hard sell. Everybody resonated with the notion that we are in a position to give back in some fashion, we want to have impact, and we all know what got us to where we are in the first place. So it was a no-brainer. Plus, Massachusetts and Boston represent environments that are conducive to investment in education improvement. The Commonwealth has embraced education reform since the mid-90s, and the city at various points in time under various mayors has demonstrated an interest. As has the business and civic community.

What we didn’t see were any predominantly black organizations that were investing. We saw a lot of organizations that were doing programmatic activity―very good work―but we wanted to create a fund so that we could bring not only ideas to the various tables in town, but bring resources to put behind ideas that we thought were important. We felt that was the unique advantage of building a fund. In the end, you know and I know that it’s fine to bring great ideas to the table, but if you can bring resources to implement them or back them up, then you’re going to have a much more influential place at that table. We just hadn’t narrowed it down at the start.

|

In the Conversation In order of appearance: Wendell Knox Former President + CEO, Abt Associates Ronald Ferguson Director, Achievement Gap Institute Mari Barrera Executive Director, Boston Basics Campaign Ruth-Ellen Fitch Former President + CEO, The Dimock Center Turahn Dorsey Chief of Education, Boston Margot Tyler Social Venture Advisor/Education Strategist, Strategic Consulting Network Jeff Howard Founder + President, Efficacy Institute |

TBF: There’s a pretty wide band of things to choose from in “education.”

WK: Exactly. Education is a broad topic, many dimensions across the continuum of birth through the workplace, really. So we decided in 2012 or 2013 that we were going to be more systematic about choosing a focal area. We decided to bring in some education experts to talk to our board of trustees. And after the first meeting―I think that took place in the fall of 2013―where Laura Perille from Edvestors (the Boston Foundation helped them get their start) and someone from the Boston Public Schools, who was intimately involved with the various initiatives and data in particular, spoke to our trustees. We got so much knowledge from their perspective on the education landscape of Greater Boston, we said, “We’ve got to do more of these!” And not only should we have more such talks but we ought to start inviting other folks who might have an interest. People we might want to invite to invest in the fund and maybe join the board and so on.

So we got a room over at Simmons College and invited folks from our various networks. Thirty-some people showed up one Sunday afternoon and we had a very rich discussion, and people brought ideas as well as information, about what the Black Philanthropy Fund should consider engaging in. We ended up doing five of those during the course of 2013–2014. We dubbed them Learning & Leadership Forums. That group grew to probably 70-some people and we had speakers from all across the education spectrum: former secretaries of education, Commissioner Mitch Chester, principals of schools that were turning around in Boston, people from a variety of sectors―civic, business and public―that were in one way or another involved in education. And one of those was Ron Ferguson. After we did five forums―that brought us to June of 2014―we decided, OK, we’ve heard all of this, we’ve gotten really educated...we’ve got to make some choices!

TBF: That must have been hard.

WK: Yes! One partnership that emerged along the way was with WGBH; [CEO] John Abbott actually spoke at one of our forums. John let us use one of his conference rooms over at ’GBH. Our board of trustees invited a lot of the speakers and participants from our Learning & Leadership Forums to bring their ideas. We asked them to discipline that a little bit, by writing a two- or three-page prospectus on an idea that they thought we should consider investing in. We got almost a dozen very thoughtful inputs. We invited those folks to come and present their ideas to the trustees and defend and argue for them, which they did. It was a very rich set of discussions at ’GBH that day. Then the trustees chose a couple of things to invest in. One of them was Ron Ferguson’s initiative. The other was a more generalized notion of investing in new initiatives that had their genesis in the community. Over time those two things merged into one.

What we were investing in specifically with Ferguson was additional support of a small Kellogg grant he had to test out his fundamental five parenting behaviors in the Dudley neighborhood. We kept talking about it and realized that, well, many of us who have been in policy research for years know that you can invest in a small pilot in a contained geography and produce any kind of result you want. Typically you overinvest. You produce results that look impressive but the real problem is you can’t bring it to scale at that level of investment. I’ve seen that through my government evaluation work, focusing on lots of pilot programs over the years. So we said, look, the real test is not whether you can roll this out in the Dudley neighborhood and get parents engaged, but can you bring it to scale? So we convinced him―long story short―let’s go big. We know the underlying science is sound, all the brain research and the work that he and his colleagues had done to distill these behaviors is sound. So Ron teamed up with us with the commitment to bring this to scale in the city. If we could really prove this out at that scale―and Boston, for all the reasons we discussed already, was an ideal test bed―maybe we could even take it farther.

[Ron Ferguson arrives.]

So we formed a partnership between the Achievement Gap Initiative led by Ron and the Black Philanthropy Fund, and along the way we collected some other partners. I mentioned ’GBH. City of Boston. Rahn Dorsey, the mayor’s chief of education, was actually one of the founders of the Black Philanthropy Fund. He was on our board before the mayor scooped him away from us (but we said, we’ll take advantage of that!). Ron introduced us to Dr. Barry Zuckerman at Boston Medical Center and BMC became involved. And we found a good friend in Jeri Robinson over at the Boston Children’s Museum through a meeting there, and we said, We’ve got to get Jeri on board! So Jeri became both a member of the Black Philanthropy Fund board and the Museum became one of our core six partners―and a standard meeting place.

So that’s how we came together. The intellectual underpinning of this is Ron’s work, which he continues to do and continues to develop. And we’ve helped raising money and with ideas for packaging and communications and awareness building. We collectively came up with the idea for these videos [gesturing to screen with video playing in background].

TBF: Hello Ron. Can you talk about how the Black Philanthropy Fund has furthered your work?

Ron Ferguson (RF): Right before the Black Philanthropy Fund decided to support us, I’d been working for about three and a half years trying to find interest, and every place I talked, foundations always said, “Great idea, but it’s unproven, so we’ll wait.” Finally, just before [the Black Philanthropy Fund] came along, the Kellogg Foundation had said, well, we’ll help you in one neighborhood. The Barr Foundation had kind of sustained us for a year while we were trying to find bigger funding. So right after the Kellogg Foundation commitment, the Black Philanthropy Fund was holding events and looking for something to get excited about. They decided they would invest a bit in helping us with the first neighborhood, but they soon came back and said, wait a minute, this is too big, too important, we want to do it citywide and we want to lead it. A lot of their contacts have helped us to get in to all these institutions around the city; we have spent the last 18 months meeting with CEOs and leaders of various organizations and businesses.

WK: Partnerships are really the key to our being able to take this citywide. Developing various kinds of funding, programmatic and distribution partnerships…. The whole strategy is to mobilize the existing infrastructure of the city, not try to create a new infrastructure.

RF: We’re not trying to create any new programs. Places can do this without hiring any new staff. It’s simply changing the conversations that are already happening. It’s trying to change the routines in organizations where people already are interacting with people they trust, so the messages are being delivered―and reinforced―by trusted people.

WK: [pointing at video in background] See up there? This is the Spanish version of our outreach video. That’s Dr. Delgado, the pediatrician at the Whittier Street Community Health Center; that’s an example of a partnership, and Delgado is doing the narration for this video. WGBH: the partner that produced it. Black Philanthropy Fund: the partner that funded it. We also did this in English, with [Ferguson’s] narration.

RF: Dr. Delgado stepped up. He did that for free. I said, “Have you ever done this before?” “No,” he said, “but I can do it!” And he did fine, he did well!

We also have videos in Haitian Creole, where our narrator is a faculty member at MIT, whose life mission it is to elevate Haitian Creole as an accepted language. There’s not much written in it, and he wants to turn it into a spoken and written language, so with the Haitian Creole videos we’ve got two versions of the subtitles. He’s the narrator, but you’ve got one version subtitled in English, and another version subtitled in Haitian Creole. He’s posted them on Facebook in Haiti. And he’s using them to build the language here. For example, there are Haitian families in Boston where the parents speak the language; the kids have heard it but aren’t really into it. So now they can hear it and read the subtitles in English and follow along. Similarly people who speak the language but have never written it or read it can look at the subtitles in Haitian Creole as they hear it.

WK: I’ve got a good friend who was a vice president at Abt for years―she speaks the language, and volunteers in Haiti every year at a school. She was telling me about this school, and I said, “You know, you should think about the Boston Basics…” and she said, “Oh! They’re already using that!”

RF: There are about a dozen other cities now that just have their own name in front of the Basics.

WK: Chattanooga Basics.

RF: Yonkers Basics. The state of North Carolina is the Palmetto State, so they’ve got the Palmetto Basics with about three counties involved now, and they’re spreading it.

WK: Ron speaks in various forums literally around the world and certainly all over the country and he’s of course mentioned the Boston Basics among the other things that he’s doing, and people pick up on it. It’s such an appealing, simple but powerful, straightforward notion that people just get it quickly.

RF: Yes, one of our phrases is socio-ecological saturation. People live in social ecologies where they are interacting and interdependent with other people. Part of the notion here is we’re not just delivering videos and booklets to people to read and look at on their own. We want their whole socio-ecological niche to support it. Sometimes you talk about the “care circle.” So Grandma is reminding you, and your uncle knows you’re supposed to be doing it, and your doctor is reminding you, and your minister is doing sermons that mention it. Right? So you can’t get away from it and it’s surrounding you. I did a presentation for people from eight nations during a weeklong workshop at Harvard on scaling up early childhood interventions. It was sponsored by the Bernard Van Leer Foundation from the Netherlands. And after I did this early in the week, people couldn’t stop talking about socio-ecological saturation. So now the Van Leer Foundation is interested because [people from] all those countries are coming back and saying, “We’re interested.” For example, Brazil: I presented in Brazil almost two years ago, and they already started using some of the ideas. There’s an article online in Brazilian Portuguese that summarizes the Basics. Now there’s interest in starting in Recife, Brazil―so it’s Recife Basics―and not long after that they’ll go to São Paolo. The country has a home visiting program with its own curriculum in Brazil, and there’s talk of using some of the Boston Basics in their national home visiting program.

TBF: You’ve started something amazing. It’s one of those things that makes you say, “Why didn’t we think of that before?” But it needs to be presented as a whole.

WK: A lot of folks when they first hear about the five Boston Basics start to kind of grade themselves. Did I do that? Well, I did this, but I didn’t know about that part…. The one I love is Read and discuss stories. Everyone in my circle says, “I read to my kids.” But most of us have to admit, we told them to be quiet and listen rather than engaging in the discussion―that they usually tried to start. But we didn’t know that that part was so important. So even these very simple nuggets―the science has added value to these things.

RF: With babies and even toddlers, it’s not about reading the book. With babies it’s about pointing to the pictures and talking with expression and letting the baby handle the book. With toddlers, it’s sort of about reading the story but if they get impatient, then fine, put it down. If they want to turn the page before you finish reading, that’s fine. It’s about having a positive experience, developing a positive relationship to books for kids.

WK: One of the things I think is very important to capture is that, when people we’ve talked to about funding and other involvement say, “Well, we’re already working on education; we’re working on K–12,” this sets up an artificial differentiation. We say, this is K–12. This is laying the foundation. Because a lot of K–12, particularly in urban and disadvantaged areas, starts out trying to deal with the kids and their achievement gaps as presented. Much of their investment goes in to trying to fix a problem that has already emerged by the time the kid first gets to school. Rather than investing in a fix, we’re trying to invest in preventing the problem, so that all of our K–12 investment can go toward advancing the kids rather than remediation. In that sense, working at this end of the continuum―right at the very beginning―is an investment in K–12. That’s an important message that some folks don’t readily get.

[Mari Barrera joins the group.]

RF: That’s what really inspired me to do this, when I saw how big the gaps were by the age of two. Eighty percent of brain growth happens by the age of two. That’s one of the catchy facts that are part of the story. In fact, the stuff that’s happening in utero is becoming better known―like that babies can hear three months before they’re born, maybe earlier. And that your mother’s voice is the clearest thing you can hear when you’re in the womb. Other voices are muffled, having to get through all that tissue, but your mother’s voice is coming down in a way that’s more clear. So newborns prefer their mother’s voice. There’s a great TED talk online, about French and German babies, explaining how they’ve documented that babies cry in the rhythm of the mother’s native language. One baby’s whimper ends in an uptick and another’s whimper ends in a downtick in a way that’s reflective of the patterns of the French and German languages. So we learn that they’re encoding language even prenatally. A lot of people think you can talk baby talk, gibberish or not at all to very little kids because they don’t know what you’re talking about. But through the Boston Basics we want them to know babies are learning the real patterns of spoken language.

WK: When we started hearing this at the Black Philanthropy Fund, learning from Ron, we realized the science is pretty clear: We know what’s important. And yet we see that most parents and caregivers don’t know that. It therefore became not only a program opportunity; it became a moral imperative to get this information into the knowledge base of every parent and caregiver. Because a lot of folks very dutifully see to their kids’ health. Buy them nice toys. Buy them nice food and keep them happy. And then they say, “I’m going to send them to a nice school when they’re ready.” Guess what? They were ready in the womb. And that was the opportunity that was being missed.

RF: When people hear us talking about this, they assume that we’re most concerned about the poorest of the poor―and of course we are, somewhat―but these issues are universal. So this is a universal campaign. We’re not trying to segment the community.

WK: That’s right. When we say Boston, we mean all of Boston. And as other communities embrace it, we’re encouraging that. This is something that everybody can benefit from.

TBF: It applies to everyone.

RF: It’s unifying. It spurs the well-to-do to perceive themselves as having a lot in common with poor folks and it gives poor folks a way to feel included with the rest of society, and not always at one end of that continuum. People at all levels have pointed out elements they didn’t know. We’ve got some nice little videos we did with mothers who encountered us through a home visiting program, and they’re talking about what they do differently and how their kids are responding. One said, “I didn’t know how important it was to just go with him to the park and watch him explore.” And I doubt she was talking about exploration before. But now she’s talking about what she sees her kid doing. Another talks about just not knowing that it was really important to pay attention to your kids and talk with them and read with them―as much as it is. And so she talked about how she does it more now. And both of them describe it almost as though their kids were asleep before and now they‘ve woken up. “Oh, they’re just talking all the time, and when I read the book they’re imagining and embellishing the story.”

Mari Barrera (MB): I want to make sure we capture one thing, which is that the moms visibly had a sense of “I did this. Look at the impact I am having.”

RF: Yes, you could see the pride.

MB: You could. It just emanated from them. This sense of, “I can do this!” And I think that sense of agency, particularly for low-income parents, who may not have that sense often, is really important.

RF: That’s interesting. It is a blend of agency and surprise, right? Surprise at what a difference it made, and pride in their feeling that they were able to make it happen.

MB: Yes. I think that’s right. I want to figure out how to tap into that agency. At least to call it out, and say that’s fabulous, the difference, and just reemphasize and support that. As part of that “saturation” that you talk about.

[Ruth-Ellen Fitch joins the group.]

WK: We should talk a little bit about the campaign aspect of this. The goal here is to make sure that every parent and caregiver in the city of Boston is made aware of this information. And encouraged to adopt these practices, right?

RF: And is surrounded by encouragement, additional encouragement.

WK: That’s what this whole saturation strategy is about. We want to get every institution that touches parents and caregivers, families in general, to be aware of this, to integrate it into their existing service relationships or customer relationships for parents.

RF: And informal, family and social relationships.

WK: Exactly. That’s why we’re taking it to hospitals. All the hospitals are involved, community-based health centers, the public library system and the mayor’s various offices, including the Boston Centers for Youth and Family. Home for Little Wanderers, Horizons for Homeless Children… barbershops! Beauticians, churches. You think of an institution or an enterprise or a business that touches families in any way, they are a candidate partner. So far we’ve got over 100 delivery sites. Some of them are parts of larger organizations.

Ruth-Ellen Fitch (R-EF): Police stations. That’s an important one.

RF: We kicked off the Week of the Young Child at the precinct station in Mattapan, with us and the mayor and the police chief, Commissioner Evans. And we talked for about a half an hour; it was during roll call, so we had about 30 police officers who were at the beginning of their day.

TBF: Brilliant. What do you say to them?

RF: We’re really engaging them to be emissaries.

R-EF: Use the techniques!

RF: We give them hand-outs.

WK: We want them to be partners. So we go out and develop partner relationships with all these institutions. In some cases it’s “retail,” one health center at a time; in some cases it’s “wholesale,” like the Boston Public Library: When [BPL President] Dave Leonard came in, we got him to agree to get the whole 24-branch system to engage. The Mass League of Community Health Centers is now engaged.

[Rahn Dorsey and Jeff Howard join the group.]

TBF: Great! This is a very impressive crew here. So I think you will have success. How will you follow up and measure that success?

RF: A few different ways. The ultimate success is to change the trendline in school readiness. The district has been gathering data on school readiness for years now, including sometimes preschool readiness. And if you just chart that line, project it forward two or three, four years from now, does the line start to move up? That’s the ultimate measure of success. In the meantime, we have debriefings of people who’ve been engaged in home visiting. We have a survey we use at the end of home visits to see what their impression is about what they’ve been doing.

We’re also working on an app that will be up for the first three years of a kid’s life―156 weeks with the app―and the evaluation of the app will initially just track the implementation, but then after that we’ll look at the impact on people who are using the app in terms of behaviors with their kids. There’s a project at the University of Chicago, looking at the impact of watching our videos. So lots of little studies done inside the project, and that overall school readiness trend that we’re looking at. We’re talking to the Brazelton Center at Children’s Hospital, about potentially doing the app evaluation. We’re continually trying to pull together the money to do all the things on our menu.

TBF: So that’s were the Black Philanthropy Fund comes in.

WK: And the Boston Foundation. And a variety of other organizations around town: Partners Healthcare has helped with funding, a variety of other family foundations have been very helpful. Eastern Bank has given funding.

[Margot Turner joins the group.]

TBF: How is the mayor’s office of education participating in this?

Rahn Dorsey (RD): Well, along with this whole group I participated in developing the initial outreach strategy for the Boston Basics―really thinking about how this fit into a citywide plan for pre-K to career education in Boston. Two huge priorities for the mayor: One, that every child in the city get off to a great start, meaning that the minute that they are born they’ve got the right developmental supports, and they get the right learning supports, as well. And two, making sure that we activate the entire community to support learning. Boston Basics was really at the nexus of those two priorities for the mayor. So this was a no-brainer for him in terms of making sure that he was a partner in using the city’s apparatus and relevant government departments to support the Boston Basics; for example, Boston Centers for Youth and Families for parent trainings, and BPS’s Countdown to Kindergarten is doing quite a bit of outreach for us as well. Our communications apparatus has been partnering with the Boston Basics to make sure that we’re reaching communities and that we’re leveraging our community partners to make sure we’re at the table as we’re looking at health care, we’re looking at churches, and figuring out the saturation piece.

TBF: Yes, using the already built infrastructure.

RD: That’s right. It was clear we didn’t need a new organization. Government offered a big platform to reach a number of citizens. So we’re still trying to figure out how we’re going to bring more of the government apparatus in to the campaign.

TBF: That’s really great. Would you each like to add anything about your particular angle on the whole project?

MB: I’m most focused on figuring out how we deliver the right training―actual training to the staff at some of these different agencies and organizations that we’ve been talking about―and support for them to introduce the Basics to their patients, their customers, their clients. And how do we at the same time help them collect a little bit of data for us, like how many families are you touching each week, or how do people respond the next time they come in and are talking to you if you say, “Have you watched that movie?” or “Have you done any of this?” Is there any ongoing engagement we can help staff have or support them to have or that will help them over time reach the people they’re serving. That is how we’re going to get this delivered quickly.

We’re also talking about developing the idea of a toolkit. We have a number of tools and everything is free of charge. We’ve got posters, we’ve got booklets, we’ve got all the different videos. All in multiple languages as we raise money to translate and interpret. So this toolkit is really going to be focused on showing healthcare professionals in every role: Here’s an RN in Labor & Delivery watching a video about an RN in Boston Medical Center who’s actually showing a family, before they depart with their newborn, a video on her iPad and talking with them about it. So then the RNs in different community health centers and hospitals can go, “I see that; I could do that.” They’ll come up with their own as well, but it’s a kick start for them. So, in every level of staffing and even volunteers, even in waiting rooms perhaps, showing them how they could teach and engage people with the Basics.

RF: Let me insert one little fact. Last week we sent around an email inviting our hospital and health center partners to be in these short, demonstration videos. There must have been eight different organizations I sent it to. Six of the eight responded within three hours, and the others responded within three days.

MB: These are CEOs of hospitals.

RF: Everybody said we want to help you. They didn’t quite know how they were going to do it, but they wanted—

WK: People get this. The health-care sector in particular sees this not as just a good community thing to do. They see the strategic value to health care in getting kids and their families engaged in development right from the very beginning. But they’re also envisioning 20–25 years out: better educated consumers of health care. More efficient consumers and people who engage in preventative behavior and who know that it’s probably not the emergency room you go to for routine care.

RF: For the providers too: They see these kids and fall in love with them, and they want them to come back as healthy adults.

WK: That’s right. Exactly. It fits the missions of all the organizations we work with. Health care in particular kind of jumped all over it right away.

MB: Can I add one thing to what Ron said earlier? All of the staff we’re talking to―when we go to Children’s or BMC or any of these institutions where we talk to the staff about the Basics and how to share them―most of these folks are parents. And they all think, “I didn’t do that…” or, “That’s what I should do.” Grandparents, aunts and uncles, everyone has got someone in their life who’s this tall and under, and to your point, a lot of us don’t know this intuitively. No matter how well I was read to, I didn’t read and discuss with my kids. I just read to the kids. So there’s a piece where you think, “Ach, I should have done it differently.” I think it’s proof of how universal this really is.

RF: With each of the five Basics there’s that little missing piece.

WK: You know we’ve talked about partners mostly in public sector terms or civic terms, service delivery organizations, but we’re also outreaching to employers. We’ve got two employers that we’re discussing pilots with to integrate the Boston Basics messaging into their benefits and wellness programs: Eastern Bank and Partners Healthcare Systems. All of the major companies in this town would likely see a benefit in sharing this information with their employee base. We’re going to try a test case with those two employers and then see if we can roll it out citywide through yet another channel.

R-EF: I’m a lawyer, so I do basics for Basics. I worked on the incorporation under Massachusetts law, and I’m working on the tax exempt status―well, we’ve got the tax exempt status and we’re working on it with the IRS, the 501c3 exemption. That’s my contribution, as well as being a cheerleader.

MB: And she ran this institution [the Dimock Center]!

R-EF: Yes, I ran this place for nine years. Then I was a partner in a law firm for a lot of years. But this is what I’m doing for Boston Basics. I’m making sure that we’re the entity that withstands any challenges and complies with the law.

TBF: Which is great.

Jeff Howard (JH): Thank you, Ruth-Ellen!

RF: You see we’re talking about people who come with a lot of social capital.

Margot Tyler (MT): I’ve worked at almost every level of education, from middle school all the way through professional development. And I have witnessed and understand that there is a fault line that gets created by the things that you miss as a child. I can see evidence of it once students get to college and I see evidence of it in the corporate world. So I just have come to the personal conclusion that this is where the work has to be done. I’ve probably spent half of my career dealing with issues around the achievement gap, managing and putting equity into the situation but a lot of that is after the fact. A lot of it is too late―by the time they get to college or high school we’ve missed 30–40 percent of the students. Dropped out or dropped by the side. So I know personally and professionally that this is where the core of the work has to be done.

I’ve spent the last 10 years working in philanthropy, so I have been working with the team to figure out the calculus of how to engage partners and others to invest in the work, whether it’s financial investment or social capital. I’m also very passionate about its being online and open source. Perhaps because of living in a community where I see many young people having children, and really not knowing how to navigate that, I see that as a tool that can permeate and create a viral environment for this message to spread irrespective of the institutional structures, just on a person-to-person basis. Particularly with young people.

TBF: That’s a good point. Meet them where they are.

JH: I was an early advocate of moving beyond the Black Philanthropy Fund’s original intention, which was to give Ron a small grant [for helping test the idea in a neighborhood] because we were impressed with the project. It occurred to me that this could be a project where we could really apply our social capital to help advance something. I reached out to Ron to find out whether he were interested in having us come on as partners. It didn’t take much persuasion, and he was actively interested in the idea. So four of us made up the first group strategizing how we could take this farther. It was renamed―and I’m proud to say it was my brainchild―people really liked the name, and I think that might have actually helped. First Basics, and then connecting it to Boston. And it’s alliterative!

TBF: Very catchy!

JH: In general, through Ron’s work, the intellectual property was there. We were attracted to it because it was so clean and so simple and so compelling. (And we talked about how we all thought about our own parenting, and thought about kids that we know.) So that was already in place. What this initial group did was start thinking strategically about how to roll it out in the city and beyond. I think we’re all kind of proud of having come up with a framework that made sense. That has worked. It’s taken a lot of work. Call that phase 2. We’ve since been joined by a lot of additional people who really are helping think about the next phase, which is institutionalizing it in Boston and taking it to the country. We’ve got some projects we’re working on now; Ron is working with several cities already. We’re packaging the Basics as the Houston Basics, the Chattanooga Basics, and getting people with means to fund that. We’re also talking about a television project that could present this in a national television venue where people could get to see what this is.

Looking at all of the ways we are able to use our skills and social capital for something so “basic” but so crucial, it’s almost as though all of our careers up to now were in preparation for this.