The Power and Potential for Boston's "Public Realm"

Our public places historically have played a major role in Boston's identity - and they should in the future, too.

February 11, 2019

By F. Philip Barash, Boston Foundation Fellow in Design and Culture

This essay originally appeared in CommonWealth, with the title "Public Spaces Define Our Identity."

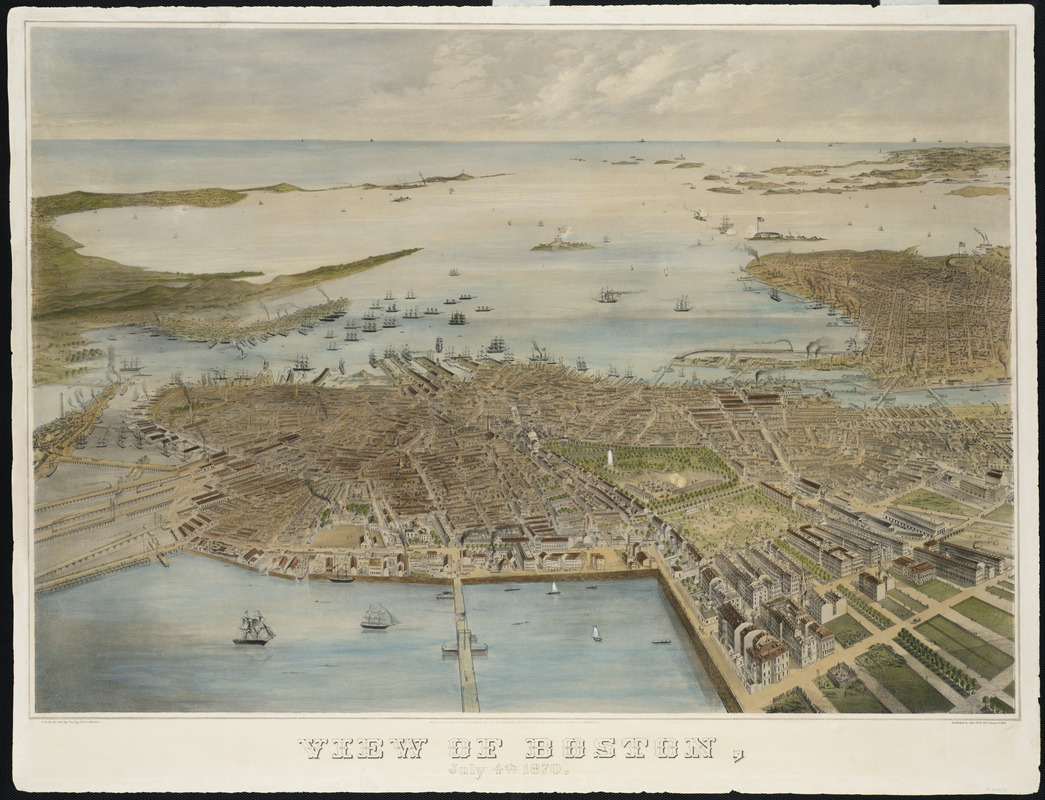

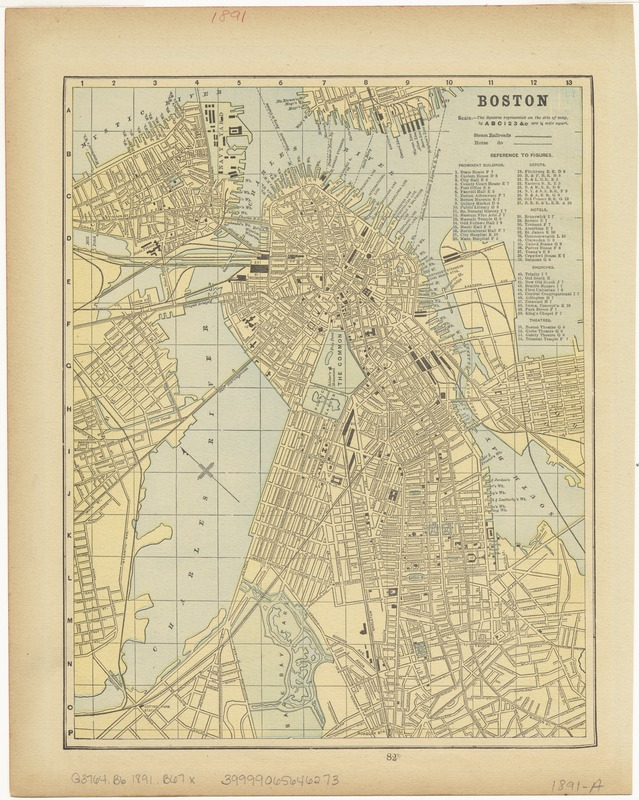

Something at a recent exhibit at the Boston Public Library’s Leventhal Map Center caught my eye. In the dozens of maps that trace the city’s history over the centuries since its founding, mapmakers reflect the desires, values, and anxieties of their time. As decades pass, filling a marshy peninsula with new people and ideas, maps show a succession of cities: first a safe harbor, then seat of naval power; first a refuge for the pious, then place of religious tolerance; first a distant citadel, then global commercial center. Smokestacks replace masts, infrastructure paves over swamp, and rows of houses, factories, and skyscrapers remake the skyline. Through all the changes, one feature of Boston is immutable: that great swath of open space in the heart of the city.

Maps are not objective records. They are documents that reveal a great deal about the people that produce them. That generation after generation of mapmakers situated the Boston Common, and later the Public Garden, at the center of the frame is a striking reminder of how large the public realm looms in our imagination. Mapmakers went out of their way to draw Boston this way: The location of the Common is privileged not because it is geographically central to the city, but because it is central to its identity.

This succession of maps inscribe the belief that remains with us today: More than naval might, more than religious freedom, more than private enterprise, our collective identity is formed in the spaces that belong to everyone. If our individual lives are lived behind closed doors, our common identity begins at the threshold.

Today, these legacy public spaces still play a central role. In fact, their role has expanded in recent years: As cities become more dense and diverse, public spaces are expected to perform multiple social functions. No longer used solely for respite or recreation, they accommodate vital community needs, from special events to casual lunches, from celebrations to protests. They are places where people come to express their will, eat lunch, experience culture. They are the connective social fabric of the city. In a 2018 book, Staging Urban Landscapes: The Activation and Curation of Flexible Public Spaces, I argue, in a chapter co-written with landscape architect Gina Ford, that public spaces evoke the “urban sublime” — that, in forcing us to encounter strangers and make ourselves more vulnerable, they put us powerfully in contact with otherness. As cities are fissured by economic disparity, racial animus, and political shortsightedness, the public realm is a vital stage for coming together, whether in conflict or communion.

Though the public realm has long served as the center of Boston’s identity and civic life, it faces marginalization. For all its importance, the public realm isn’t lavished with the kind of attention and funding that private real estate development tends to attract. Paradoxically, the spaces that unite us are often afterthoughts, leftovers from development. Today, Boston is in the throes of a building boom, its physical shape and social geography in flux, its civic fabric stretched thin. Although we Bostonians recognize this challenge, we address it primarily through the vocabulary of housing or resilience or economic development. But what’s required is a broader view of the role of the public realm in structuring the cityscape and the civic life it supports.

In Boston, no one organization has emerged as the champion of an inclusive, vibrant public realm. But the need for such a champion is apparent and urgent. This is why I am gratified that the Boston Foundation is taking a deliberate step in defining this opportunity and exploring the most promising levers of change. In a city where disciplinary design resources are bountiful — think of architecture programs, trade associations such as the Boston Society of Architects, etc. — but residents continue to express disenfranchisement from the forces that shape their communities, the Boston Foundation occupies a unique position as a convener and honest broker of multiple, at times divergent, interests.

The foundation’s interest in the public realm can have a formative influence in a nascent conversation at a time when Boston is undergoing dramatic changes. In representing public interest in the design and animation of the public realm, the foundation can insist on including diverse voices from within — and outside — of the design establishment in key decisions. It can also foster a more open (and more loud) dialogue about the role of the public realm in civic life. As Boston is being remade, the Boston Foundation has the chance to encourage the creation of exemplary public spaces — beautiful, activated, and welcoming.

There is not one single, universal way of achieving this outcome. In cities across the US and around the world, leaders like the Boston Foundation — and the civic ecosystems they serve — have explored a range of approaches. In San Francisco, for instance, land banks and policy institutions such as SPUR have systematically argued for setting aside space for public benefit.

In New York, a cohort of organizations, including the Design Trust for Public Space, Van Alen Institute, and others, are embedding design thinking into municipal and community-based agencies. And in Chicago, a robust dialogue among critics, curators, and public education nonprofits (like my alma mater, the Chicago Architecture Center) ensures that design decisions with implications on the public interest are vetted openly and inclusively. Boston can benefit by learning from its peers while forging a new model for enhancing and activating the public realm. In the months and years to come, as a fellow at the Boston Foundation, I will be working closely with community advocates, design experts, the media, educators, open space wonks, City Hall, and others who have a stake in the public realm to identify the most effective ideas, and, ultimately, to formulate a philanthropic and policy strategy.

Long before the advent of drones, before planes, dirigibles, and hot air balloons, mapmakers had to rely on their imaginations to float above the metropolis. Their maps are testaments to vision and aspiration — not cartographic precision. We have much to learn from their example. For at stake is more than just the preservation of iconic public spaces like the Boston Common. When we protect public places, when we insist on better design, when we empower people to participate in making their own city, when we lay the foundations for civic life, we are investing in what is yet to be seen.