The Greater Boston Area faces a range of issues, from rising housing costs, to residential segregation, to underinvestment of the MBTA, to climate change impacts due to car-centric planning.

Boston Indicators and TransitMatters collaborated to produce the report, Transit-Supportive Density in Greater Boston, released earlier this year. The study explores how we in the Greater Boston Area can address these challenges by aligning housing and transit policy to unlock a “virtuous cycle” of investment in both housing and public transportation.

In order to do this, the report explores the following questions:

- What levels of housing and employment density are necessary to support high-functioning transit?

- Where in North America has this been done well? What can we learn from them in Greater Boston?

- How dense are station areas across Greater Boston today?

- How does our transit system enable or limit density?

- What types of station areas are best positioned for growth in transit-supportive density efforts?

The authors also look at local to international examples of where this work can be done and is being done, and what we can do to further advance this goal.

What is Transit-Supportive Density, Anyway?

To develop dense, walkable neighborhoods, transit-supportive density (TSD) is a school of thought that highlights the “critical role that housing density near transit plays in fostering virtuous cycles of investment and positive-sum growth.”

In other words, building enough housing near transit to sustain a safe, frequent, reliable, accessible transit system, or the key link between transit-oriented development and strong ridership.

In the report’s words, “a growing body of evidence shows that increasing population density around transit hubs is essential for creating the human capital and economic dynamism that support thriving neighborhoods with reliable, well-funded transit service.”

Increased housing and increased public transit usage translates to increased climate, mobility, racial, economic, and health justice. When people have a roof over their heads near affordable means of transportation that emit less carbon into the atmosphere, they experience a higher quality of life which allows them to live happier, healthier lives.

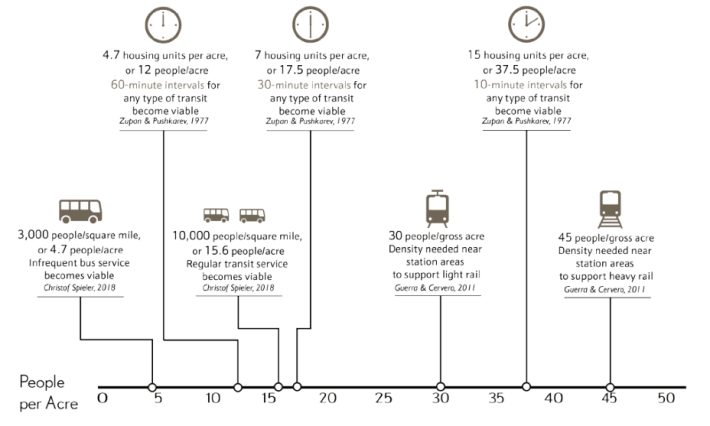

While definitions vary slightly depending on the agency, the report pulls research from U.S. and international sources to provide the following benchmarks, representing the minimum levels of residential density needed to justify different levels of transit:

- Moderate-Frequency Service - 15 people per acre, or 6 housing units per acre

- High-Frequency Service - 40 people per acre, or 16 housing units per acre

Forest Hills has access to the Orange Line, the Commuter Rail, the bus, and the Southwest Corridor bike path, but does not meet the housing density threshold for frequent transit service (11.8 units per acre).

While recent developments like AO Flats, Velo Forest Hills, and MetroMark have added 600+ units, showing progress toward transit-supportive density in the area, the area remains relatively low-density and could stand to develop more units on sites like the MBTA's Arborway bus yard – without the threat of displacing current residents.

How Does Massachusetts Measure Up?

At this point? Not too well.

According to the report, at least 15 people per acre are needed to sustain moderate transit service. When that’s kicked up to high-capacity service – like the Red Line or Commuter Rail running every 15 minutes – the area needs closer to 40 people per acre (or 16 housing units per acre).

Currently, MBTA Rapid Transit (Red, Orange, Green, Blue, Silver) station areas average only 11.8 housing units per acre, with Commuter Rail station areas at a low 3.2 units per acre.

When looking at suburban and Gateway Cities, the density around those stations falls below the minimum 6-unit-per-acre threshold that experts say is needed to support even basic service.

This snapshot of the Greater Boston Area reinforces the impact of car dependency and how it exacerbates urban sprawl and exclusionary housing development and zoning.

The report highlights Jersey City, the NoMa neighborhood of Washington D.C., the Greater Toronto Area, and Vancouver as areas across North America that have leaned into and benefit from transit-supportive density.

- In Jersey City, over 4,000 units have been built near Journal Square since 2010, which has transformed a PATH station into a hub of housing, jobs, and retail.

- NoMa in Washington D.C. has grown by 7,300 units of housing and over 40,000 jobs after the development of a single Metro station in 2004.

- In the Greater Toronto Area, suburban commuter rail stations like Mimico and Mount Pleasant welcome thousands of new homes.

- The expansion of Vancouver’s SkyTrain system has sparked development in suburbs, converting them to urban hubs of their own.

These examples highlight how powerful the pairing of frequent public transportation service and inclusive land-use policy can be – developing more dense, vibrant, lively, and equitable communities.

Station areas in wealthy suburban communities remain wildly underbuilt. For example, Needham has a lot of potential to support higher levels of density with four Commuter Rail stations near its downtown, yet a ratio of 4 units per acre. However, there has been local zoning resistance stalling this progress.

The town recently rejected the MBTA Communities Compliance plan, which in part would have rezoned a vacant Carter’s building across from the Needham Heights station that has been empty since 2018. Most multifamily development has been pushed to the outskirts of town, out of the reach of transit.

The State of Transit-Supportive Density and Transit in the Greater Boston Area

Looking at the density around transit stations across the state provides insight into what must be done to align transit and land use for the benefit of residents of all walks of life.

After decades of spiraling car-centric policy, the state must reprioritize and reinvest in its transit systems and the neighborhoods they serve to unlock the full potential of the MBTA and RTAs, connecting people across the networks, across the state, increasing ridership, and giving way to increased transit-supportive density.

Rapid Transit

Greater Boston’s subway system, made up of the Red, Orange, Blue, Green, and Silver lines, is the blueprint for transit around the region. While their range stretches considerably far up and down the area, there is work to be done regarding the density of the areas it serves.

For frequent service areas (every 10-15 minutes), the benchmark is roughly 16 housing units per acre within a half-mile of stations. At this time, the MBTA’s rapid transit station areas are averaging at only 11.8 units per acre, and only half of all station areas meet the 16-unit threshold.

- The Red Line, the busiest subway line, only averages about 12.4 units per acre around its stations. More central stations like Charles/MGH are areas with high density, but more suburban areas like Braintree and the Mattapan Trolley corridor fall well below the benchmark.

- The Orange Line has the strongest showing of TSD, with an average of 19.6 units per acre, but the southern end of the line from Ruggles to Forest Hills have less housing density despite access to the Southwest Corridor Park and growing ridership.

- The Blue Line averages 14.5 units per acre. There’s very little housing available near its outer stations like Suffolk Downs, but those station areas have been approved for massive new developments in the future.

- The Green Line has more than half of its station areas meeting the 16-unit benchmark.

- The Silver Line, while technically a bus rapid transit line, has the opportunity to meet the moment in Chelsea given the line’s recent extension. There are signs near the Box District and Chelsea stations that show signs of TSD growth.

Commuter Rail

All 13 lines of the Commuter Rail stretch deep into the area’s suburbs and Gateway Cities, but the land use around its stations are a real opportunity for TSD growth.

The Commuter Rail’s station areas average just 3.2 housing units per acre, which is far below the 6 units per acre that are needed to sustain even basic, hourly transit. 102 out of the system's 134 stations fall below that benchmark.

Buses and Regional Transit Authorities (RTAs)

Outside of the rail system, buses are critical in addressing first- and last-mile gaps where trains don’t quite reach yet. The MBTA Bus Network Redesign signals progress, but bus routes continue to be constrained by traffic, inconsistent frequency, and low density around bus service areas.

RTAs, which serve regions beyond the reach of the MBTA, also have extremely low housing density in their service areas. Increasing state funding and new fare-free policies are helping RTAs launch new routes and attract more riders.

Brockton, a Gateway City with solid Commuter Rail access across three stations and lots of available land, faces weaker housing demand and financial challenges (low rents that can't cover high construction costs, regulatory hurdles, and red tape) that stunt development.

The city sits at a low 3.6-4.6 units per acre, and despite having 32 acres of developable land downtown, 46 percent of that land is dedicated to car-centric developments like parking lots. Increased development with support from the Housing Development Incentive Program (HDIP) and Affordable Homes Act would help bridge the financial gaps to produce the development needed to revitalize the city with the largest Black population in the state.

Where Do We Go From Here?

In its conclusions, the report recommends increasing transit frequency, advancing zoning reform like the MBTA Communities Act, prioritizing investments in Gateway Cities like Brockton and Lynn, where the need is high but housing market is weaker, unifing fares between systems like the Commuter Rail and the T to make transit affordable, and ensuring accessibility measures like level boarding and working elevators.

The Greater Boston Area has come a long way from horse-drawn carriages to where we are now. From the development of the first transit system in the country to redlining, exclusionary zoning, and urban sprawl, the area can come back to its roots with transit-supportive density.

The work is cut out for us, but in advancing TSD throughout our housing and transit systems, we can sustain a climate-resilient, affordable, and equitable future.

Check out the complete report here.

Weigh in in our comments section: what areas near you do you feel could benefit from TSD? What changes would make the biggest difference where you live?